Labor Day weekend is the appropriate time to post this look at neglected working class folk hero Joe Magarac. This figure was the Steel Mill equivalent of Paul Bunyan and John Henry.

Labor Day weekend is the appropriate time to post this look at neglected working class folk hero Joe Magarac. This figure was the Steel Mill equivalent of Paul Bunyan and John Henry.

Though mostly associated with Polish-American steel workers in Pittsburgh, PA the general figure of a literal “man of steel” helping and protecting his coworkers can be found from the East Coast through the American Midwest. Sometimes the figure is Croatian or some other ethnicity instead of Polish.

Written versions of Joe Magarac and/or similar steel worker tall tales seem to have started around 1930 or 1931. Oral legends about such figures – but not specifically Joe Magarac – have been dated as early as the 1890s.

Vintage advertisements from tattered old newspapers indicate that such Man of Steel imagery may have been used for the steel industry prior to World War One. This “Which came first, the chicken or the egg” dilemma for Joe Magarac and other Steel Men puts one in mind of the quandary surrounding Billiken lore.

As a lame play on words since this is Labor Day season I’ll present Joe Magarac’s origin and then depict his tales as “Labors” like in The Labors of Hercules.

As a lame play on words since this is Labor Day season I’ll present Joe Magarac’s origin and then depict his tales as “Labors” like in The Labors of Hercules.

BIRTH – Joe Magarac supposedly sprang into existence from a mound of iron ore and – depending on the version – that mound was either in Pittsburgh or the Old Country. Magarac emerged from the melting mound fully grown and spoke broken English like so many of the other Polish steel workers. He was called into being by the urgent need to catch up on production since the current shift had fallen dangerously behind.

Joe was 7 or 8 feet tall, his flesh was like solid steel, his torso was as wide as a smoke-stack and his arms were as thick as railroad ties. His surname Magarac meant “mule” in the workhorse sense, referring to his stamina. Joe’s appetite was such that he carried his lunch in a washtub instead of a standard lunch box.

Magarac’s favorite leisure time activity was polka-dancing and halushkis were his favorite food.

THE LABORS OF JOE MAGARAC: Continue reading

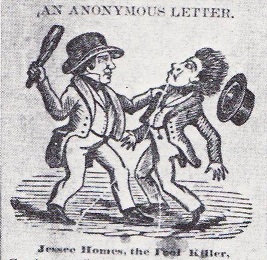

PART TWO: The second surviving Fool Killer Letter. (See Part One for an explanation)

PART TWO: The second surviving Fool Killer Letter. (See Part One for an explanation)  (My fellow geeks for 19th Century American history will recall that these routes – sometimes referred to as Star Routes because they were indicated by three stars on the route indexes – were often at the center of bidding scandals.)

(My fellow geeks for 19th Century American history will recall that these routes – sometimes referred to as Star Routes because they were indicated by three stars on the route indexes – were often at the center of bidding scandals.)  In this case the distraction came in the form of “a venerable and mighty clever man” who asked Holmes to find out who had stolen his prize turkey. Armed as always with his club/ walking stick/ cudgel the Fool Killer began his investigation.

In this case the distraction came in the form of “a venerable and mighty clever man” who asked Holmes to find out who had stolen his prize turkey. Armed as always with his club/ walking stick/ cudgel the Fool Killer began his investigation.