THE PENOBSCOT CAMPAIGN – Most sources refer to this military campaign as the Penobscot Expedition, but I feel the word campaign is far more accurate. At any rate, if it had been a success this combined land and sea effort against the British in 1779 would be hailed to this very day. Unfortunately, its failure has relegated it to the Memory Hole for most people.

This campaign was an attempt to drive the British out of the portion of Maine that they had seized and renamed New Ireland. Because Maine is central to this affair, I will first clarify a few things that some Americans as well as non-Americans can get thrown off by.

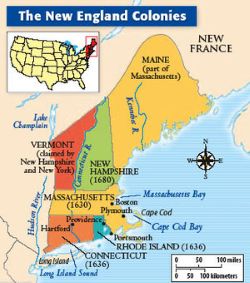

*** In general, we are all familiar with the original 13 Colonies that broke away from England during the American Revolution. Because Maine is not named among those 13 colonies, some people are confused when it is mentioned as the location for various battles of the Revolutionary War.

*** In general, we are all familiar with the original 13 Colonies that broke away from England during the American Revolution. Because Maine is not named among those 13 colonies, some people are confused when it is mentioned as the location for various battles of the Revolutionary War.

Maine was a district of Massachusetts at the time. Similarly, Kentucky was not one of the 13 Colonies, but it was a department of Virginia, which is why Daniel Morgan’s Kentucky Rifles were part of America’s army during the war.

Ohio counted as a department/ district of Pennsylvania at the time, so the battle at Chillicothe, OH was a Revolutionary War action. Vermont was not one of the 13 Colonies, but it was part of the Hampshire Grants and was being fought over by New Hampshire and New York before the war, which was why Ethan Allen’s Green Mountain Boys had originally been formed in the cause of Vermont Independence.

Moving back to 1779, the First and Second Battles of Machias, ME had already been fought years earlier. Machias and a few other ports were bases for American Privateers to continue preying on British (including Canadian) shipping AND for periodic amphibious raids on Nova Scotia and elsewhere.

On June 16th-17th, 1779 British General Francis McLean led his troops and several Loyalist American civilians in establishing what they called New Ireland. This “new colony” was to serve as an occupied stronghold for the Brits militarily and as a new settlement for Loyalists who had already fled or been driven from America’s rebellious states.

Much of Maine was wilderness at the time and McLean’s expedition erected additional fortifications on the land overlooking Penobscot Bay to reinforce Fort George on the bay’s Majabigwaduce Peninsula. America’s rebel leaders became aware of this combined military threat and attempted Loyalist Colony.

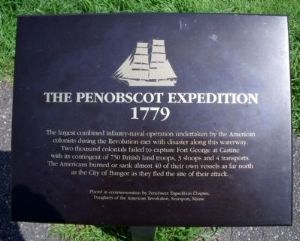

On July 19th, 1779 the Penobscot Campaign was launched with 3,000 troops and 44 ships, the largest purely American naval force assembled during the entire war. General Solomon Lovell was in command of the land forces and Commodore Dudley Saltonstall was in command of the U.S. naval forces.

On July 19th, 1779 the Penobscot Campaign was launched with 3,000 troops and 44 ships, the largest purely American naval force assembled during the entire war. General Solomon Lovell was in command of the land forces and Commodore Dudley Saltonstall was in command of the U.S. naval forces.

NOTE: The land forces included Colonel Paul Revere’s artillery units, which he had commanded since 1776.

As for the British, General McLean’s original force of “1,000 men and 2 warships” had grown to 10 warships. The Redcoats were on defense and had the advantage of fighting from behind fortifications. They would also benefit from squabbling between General Lovell and Commodore Saltonstall over how to conduct the operation.

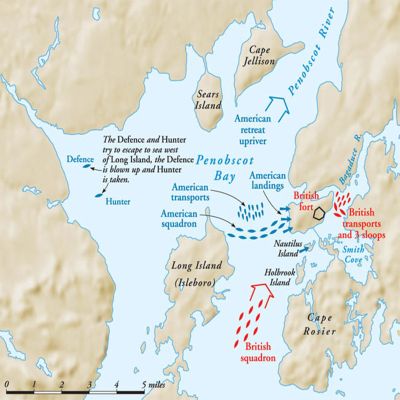

On July 24th-25th the Americans assembled at Penobscot Bay. The American and British fleets exchanged fire from roughly 3:30pm to 7:00pm on the 25th. While that was going on, an American attempt at a landing was driven off by the Redcoats.

July 26th saw a detachment of Continental Marines seize the British battery on Nautilus Island, but a simultaneous attempt by militiamen to land at Bagaduce on the peninsula was repulsed by the Brits. Meanwhile, General Lovell personally led more of his troops in a successful landing.

Though under constant fire, Lovell and his men began constructing siege works against the English. On July 27th, Lovell’s ground troops continued their siege procedures while Commodore Saltonstall’s fleet engaged the British fleet in a fierce but indecisive battle for over three hours.

July 28th found three American vessels, the Hunter, Sky Rocket and Tyrannicide, using cannon fire as cover for 400 Continental Regulars and militiamen to land at Dyce’s Head and move toward Fort George. A brutal battle against British soldiers on the heights overlooking the fort resulted.

July 28th found three American vessels, the Hunter, Sky Rocket and Tyrannicide, using cannon fire as cover for 400 Continental Regulars and militiamen to land at Dyce’s Head and move toward Fort George. A brutal battle against British soldiers on the heights overlooking the fort resulted.

The Redcoats were defeated and retreated inside the fort. General Lovell made a controversial decision to halt on the American-held heights and establish Revere’s artillery units to bombard the fort into eventual surrender rather than concentrate forces for a full assault. Of the initial 400 Americans landed at Dyce’s Head near Fort George, just under 100 had been wounded or killed.

Commodore Saltonstall was appalled at what he regarded as a needless slaughter and threatened to stop cooperation of his Continental Marines with Lovell’s land forces. Thus began the increasingly contentious relationship between the two American commanders.

The commodore’s flagship, the Warren, had suffered so much damage during the past several days of fighting that he was intimidated and nearly useless for the rest of the Penobscot Campaign. Though at this point the Americans still had naval superiority over the British, Saltonstall conducted his forces in a hopelessly timid manner, resisting requests and/or outrightly refusing to participate in General Lovell’s efforts.

Rather than attack Admiral Henry Mowatt’s naval forces to end their hold on the entrance to Penobscot Bay, Saltonstall instead established his ships just outside of firing range of the British ships. This prevented the Brits from leaving the Bay, but they didn’t want to, anyway.

The commodore’s meek strategy left the Royal Navy vessels free to continue training cannon fire on the American land forces as they continued erecting siege works and subjecting Fort George to bombardment. The Brits were also thus able to block American attempts to charge Fort George en masse.

The commodore’s meek strategy left the Royal Navy vessels free to continue training cannon fire on the American land forces as they continued erecting siege works and subjecting Fort George to bombardment. The Brits were also thus able to block American attempts to charge Fort George en masse.

Two weeks went by as Saltonstall’s inaction snatched defeat from the jaws of victory for the Americans. The commodore permitted only a few ship-to-ship exchanges during those weeks. Meanwhile, additional British warships were on the way.

Stepping back to July 30th, the land and sea forces of both sides subjected each other to a monumental day-long cannonade. The night of August 1st, General Lovell ordered an assault on the Half-Moon Battery near Fort George. The Americans won and took possession of the battery but the next day the Redcoats managed to retake it amid fierce fighting.

Varying degrees of armed clashes continued on a daily basis and on August 3rd, British Captain Sir George Collier led a relief fleet of ten warships from New York Harbor headed for Penobscot Bay.

Come August 11th, Commodore Saltonstall finally condescended to launch an all-out naval assault on Fort George but the British relief fleet under Collier arrived in time to turn the land and sea fighting entirely against the Americans.

In the ensuing disaster, American ships were captured or destroyed and the surviving ships – evacuating troops – were forced to flee up the Penobscot River while Commodore Saltonstall remained befuddled. British warships pursued the Rebels upriver and engaged in periodic firefights over the next few days.

In the ensuing disaster, American ships were captured or destroyed and the surviving ships – evacuating troops – were forced to flee up the Penobscot River while Commodore Saltonstall remained befuddled. British warships pursued the Rebels upriver and engaged in periodic firefights over the next few days.

August 14th-16th found the still-retreating Americans accepting the inevitable. They set fire to their remaining vessels to keep them out of Redcoat hands and fled south on foot toward Massachusetts proper. They carried no food or additional ammunition and many died on the overland trek home.

American dead or wounded from the tragic affair numbered 474, the British dead and wounded were estimated at 86 to just under 100. In September, Commodore Dudley Saltonstall was court-martialed and found primarily responsible for the catastrophe.

He was dismissed from the service and declared “ever after incompetent to hold a government office or state post.” Colonel Paul Revere was charged with disobedience and cowardice but was cleared of those charges during his court-martial.

Sadly, the British held on to their “New Ireland” section of Maine until withdrawing from it as part of the conditions of the 1783 peace treaty ending the Revolutionary War.

I generally consider the Penobscot action as a tragi-heroic affair like that presented during the film A Bridge Too Far‘s depiction of Operation Market Garden from World War Two. The hopeful expectations and initial successes were followed by bleak, unrelenting catastrophe.

💙

Thank you very much!

Pingback: THE PENOBSCOT CAMPAIGN: AMERICA’S REVOLUTIONARY WAR TRAGEDY – El Noticiero de Alvarez Galloso

Logged, thank you sir!

It’s really sad from the American side but it was truly a heroic action. Well shared 💐

Thank you for saying so!

😊💐

😀 😀

You just shared details my schools should have taught.

That’s a very nice thing for you to say! By the way, I gave you guys a shoutout on this blog post – https://glitternight.com/2025/06/30/truckee-meadows-community-college-cool-named-sports-teams/

I’m weakened and grateful by this. Thank you for thinking of us, our beautiful Murphy and me too. I had no idea how supportive a friend you would be when we followed your, amusing, and informative blog. I hope the Lil’ Murph calendars bring you joy each month instead of sorrow, and I sincerely and deeply appreciate you and the support of you & your wife to love and/or appreciate a Beardie whom you’ve never met, so who I tried so hard to convey the personality and character quirks of.

Thank you for such kindness. I’m very glad you were pleased with this. We will never forget Murph!

Please disregard typos. I tried to repair them & my possessed phone sent the message.

How unique… the blogger whom you’ve shared sends a wonky sort of reply🙄 One day, I’ll declare that I’ll stop using the possessed phone for comments. What an impression! It’s something I do well. I won’t be heartbroken if you delete my comments😆

Ha! I can relate to the “possessed” phone sending comments before they’ve been edited. I look forward to your comments and I would only ever delete one if you requested it be deleted!

Thank you, Edward.

I don’t want anyone to experience phone issues as I, yet strangely, I’m glad people understand what it’s like. I think Lizardplanet is receiving more views because of your shout-out 🦎

Oh, that would be great! I hope so!